Using a Time-Sharing System

I have found that the best way for me to advance my software career is not to try to advance it, not to make plans for the future, but just to find work that I really enjoy doing and do it. When my first job at Bell Labs turned out to be boring, this is what exactly what I did.

Because I wrote my Ph.D. thesis on switching circuit theory instead of on software, when I applied for a job at Bell Labs I was offered several positions in hardware design but only one in software, and that one not in research. Since I wanted to build software, with some reservations I accepted the one software job they offered me. I did not realize that at Bell Labs there was a large gulf between research and development. It was rarely possible to transfer from development to research, probably because many people wanted to be in research. You had to be hired into research directly from school.

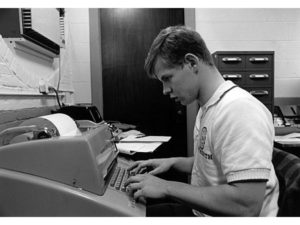

In a previous blog post I describe how I transformed my boring job with the Nike-X anti-ballistic missile project into a very exciting one: I managed to create the job of assembling a team of contract people from General Electric (GE) and building a time-sharing system (TSS).

Two years before this, Bell Labs had entered into a joint research project with MIT and GE to build a next generation TSS: MULTICS. I and my management were criticized for embarking on another TSS project when MULTICS almost certainly would be finished and available before my system. But my project had several advantages over MULTICS:

- My goal was simple: to build a TSS much like MIT’s CTSS, for use in the NIKE_X project.

- We built a prototype first: rather than tackling both a new system and a new machine (the Nick-X hardware) at once, I decided first to build a prototype on a commercial machine, the GE 635 computer.

- I had the freedom to do it my way: my management had bigger concerns and left me and my team alone to do our work.

- I was able to manage from within: as a working member of the team as well as the boss, I could guide the work and head off problems without getting in the way.

As it turned out, our TSS was completed before MULTICS. In fact, Bell Labs later abandoned the MULTICS project before it was completed.

The Nike TSS prototype was completed on time and on budget. The computer center wanted to turn it off after it was finished, since it was intended only as a prototype and they had no way to charge users for it. However, they were forced to keep it running for five years because the users insisted it was essential to their work. Ironically, the “real” TSS on the Nike-X hardware was later finished on time and on budget but it was never used.

By the time we finished the prototype I realized that I was in the wrong (for me) part of Bell Labs. The challenging work was being done in computer science research. Meanwhile I had been offered a job with GE. So, with this job offer in my pocket, I went to my management and told them I would quit unless I was transferred into computing science research. I expected to leave Bell Labs, but to my surprise research management agreed to the transfer.

At about the same time that I transferred from the Nike-X project into computing science research, two department heads and a director transferred from computing science research to the Nike-X project. The joke going around after my transfer was that it was a baseball trade: me for two department heads and a director.

Thus it was that the job I took for fun led to my work on MULTICS with Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, and several others. Out of MULTICS, the failure, came UNIX, the success. I’ll talk about this in my next post.

– Rudd Canaday (ruddcanaday.com)

– Start of blog: My adventures in software

– Previous post: Building Software Then and Now

– Next post: How C Came to Be

Share this post: data-url=””

data-via=”ruddcanaday”

data-text=””

data-count=”none”>Tweet